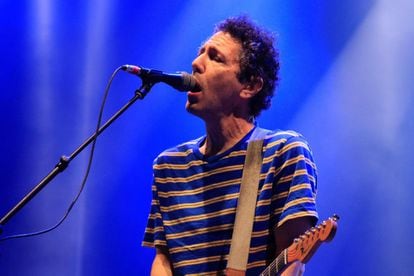

Ira Kaplan, the guitarist and singer of the U.S. indie rock band Yo La Tengo (YLT), loves soundchecks — the time before a concert that musicians usually hate, which consists of familiarizing themselves with the acoustics in the room in which they’re going to play. It’s such a tedious ritual that you’d think Kaplan, 66, says it just for fun, to offer the world an image of a modest guy, far from the tired stereotype of rock stars. But Kaplan hasn’t come back from a walk on the wild side; he never left home in the first place. “YLT was founded by a married couple, so we never went through a period of excess,” he says. “What can we do? We like monotony.”

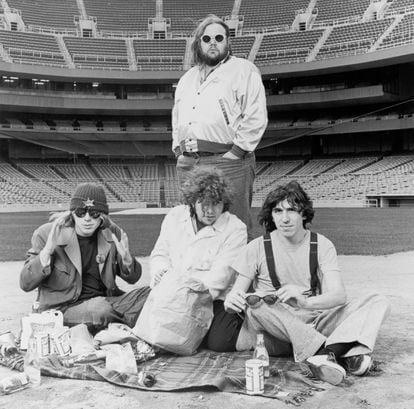

In mid-March, Kaplan was in a dressing room in the college town of Charlottesville, Virginia, a stop on the YLT tour for their great new album, This Stupid World. Outside, the rest of the band is having a great time (doing a sound test, of course): the other members of the group are drummer Georgia Hubley, Kaplan’s wife of 36 years, and James McNew, who became a permanent member in 1992, after the couple tried 15 other bassists before him. All three members of YLT are also singers.

The band’s seemingly conflict-free history, Kaplan and Hubley’s faithful marriage, the third member’s patience with disharmony and the ensemble’s longevity all make YLT unique in American rock music. Survivors of the 1980s alternative rock explosion (which included Sonic Youth, R.E.M. and Dinosaur Jr.), the band members seem comfortable feeding the mystery by keeping information to themselves in their press interviews, which are almost always done by Kaplan, sometimes by McNew, and very rarely by Hubley. “Explaining myself is not my favorite pastime,” the guitarist says at one point in the interview. At another moment, he answers “no” to the question of whether he missed life on the road during the pandemic. “It’s not my personality or the band’s personality to want what we can’t have.”

Perhaps all of that stems from the band’s masterful decision to focus its attention on the music. Theirs is an unmistakable sound in which melancholy and sweetness coexist alongside noise and fury, and whispers and a flair for pop songs combine with litanies of experimental distortion.

This year marks two anniversaries in the trio’s history: it’s been four decades since Georgia and Those Guys — YLT’s first incarnation — made its debut on stage, and 30 years since they signed to indie label Matador, another testament to the band’s loyal personality.

Gerard Cosloy, the record label’s co-owner, told EL PAÍS a couple of weeks ago in an email that he is still in awe of “their work ethic, determination and willingness to rely on the public to guide their career.” He went on to describe the relationship between YLT and Matador: “When they say ‘jump,’ we say ‘how high?’ Which has worked out better for us than Edwin Diaz.” Diaz is the New York Mets’ relief pitcher who was seriously injured while celebrating Puerto Rico’s win over the Dominican Republic in the World Baseball Classic.

There, too, they understand each other. Kaplan is a Mets fan and, if you were wondering why musicians from Frank Sinatra’s hometown of Hoboken, New Jersey, call themselves Yo La Tengo, it has to do with baseball. Once upon a time, in 1962, a player named Richie Ashburn collided with a Venezuelan teammate, Elio Chacon, who didn’t know English, when going for the ball. To avoid collisions, Ashburn learned three words in Spanish: “yo la tengo” or “I have it.”

Journalist Jesse Jarnow opened his 2012 biography of the band by discussing the confusion that the group’s name caused in the early days (Wo La Tango, Yo lo Tengo, Ya Lo Tengo). Jarnow called his book Big Day Coming, after one of the group’s most beautiful songs; in his tome, the journalist describes the music scene in which they emerged and the friendships they forged. The book is replete with anecdotes in which the reader is left waiting for a plot twist that never comes. But above all, it is an account of how marriage helped build the indie mold as a sedate derivative of the punk rock ethic.

“[In the mid-’80s], they wore Converse All-Stars, played noisy jams, sometimes sang quietly, released 7-inch records, got played on college radio, and recorded for an independent label,” writes Jarnow in Big Day Coming. In YLT’s case, time also contributed to the band’s greatness; unlike others, they didn’t have instant success. Despite this, their fidelity to a modest but important sound, which emerged in the mid-1990s, made them one of those rare bands that one knows will be able to keep going for years.

“What interested me most about their story, and what I think makes them different,” Jarnow said on Thursday in a phone interview, “is how long it took them to find their voice and learn to be themselves. Since they’ve done that, they’ve stuck to that position, but they’ve adapted to the times. Behind their timid appearance is a strong sense of confidence in their artistic commitment. I wasn’t interested in writing the story of a band like Fleetwood Mac, with all their breakups and drama. I wanted to write a book in which the music was the most important thing. YLT are first and foremost lovers of great music. And they fit into the lineage of New York sound. Ira was always there; first in the audience and then on stage. He was part of it all from a very young age.”

Punk inspiration

Kaplan explains the longevity of his relationship with New Yorker Hubley, 63, by observing that starting to play music and beginning a relationship as a couple were basically the same. “I’m not original: I decided to try to be a musician when I saw a punk concert, and I thought, ‘I could do that.’ I was convinced to try it with her. Our thing worked from the beginning. And it got better as our sound improved,” the guitarist recalls.

In 2024, the couple, who met “at a Feelies concert,” will celebrate 40 years of YLT. That milestone will be in December, a month in which they practice another of their rituals: a week of Hanukkah concerts, celebrating the Jewish holiday with comedians, bands and solo artists who are invited to join them on stage at a New York club. Tickets sell out fast, even though attendees won’t know what the lineup will be until the day of the show.

Decisions about who will play with the group are made like all the others the trio makes. Kaplan says that the band “doesn’t function as a democracy. If there’s something two of us want to do, but not the third, we don’t dishonor that person’s wishes. We’re not like those groups where everyone writes their own song and moves on to the next one. Over the years, I’ve learned that fighting, blowing up, throwing a tantrum, can be fun, yes, but it’s a very temporary emotion, which, in reality, only makes things worse,” he adds.

Beyond serving as a testament to understanding, This Stupid World — ”as you get older it’s not that the world gets stupider,” Kaplan jokes, “maybe it’s that you get smarter” — their 17th studio album sounds like a compendium of all of the phases of YLT. They recorded it during the pandemic in quarantine at the band’s Hoboken rehearsal space. They had it easier than others: two-thirds of the group were members of the same nuclear family. “And the rest could be put away,” Kaplan wryly explains.

“Rehearsal” is a “broad” concept for YLT. It might mean “talking about what we did over the weekend for a good while and then playing for the sake of playing for 10 minutes.” When it’s time for the musical part, Baltimore-born McNew, 53, always has his microphones ready to record what the trio does, which is often pure improvisation. After a certain point, they knew that all that pandemic material would end up being something; their most recent album, This Stupid World, is the first one for which they did not have an outside producer.

In the afternoon, a man intercepted Kaplan on his way to the corner record store to buy rock and soul singles; he told the musician that he had seen YLT live 27 times. In the interview, Kaplan — who was a music journalist in New York in the late 1970s and early 1980s before he was a guitarist with YLT — wasn’t overly impressed with that number. “There are bands I’ve seen far more than 27 times.” For example? “[Veteran American rock band] NRBQ. They always manage to sound different.”

Two days before that, YLT had played in Nashville, where they made news after Kaplan and McNew played their second set in drag to protest a Tennessee law aimed at restricting drag shows. “Things are getting pretty ugly in this country,” Kaplan explains. “I’m 66 years old, I’m not saying they’re worse than when I was young. But at least we had a sense that it was going to get better. I don’t get that feeling now… it’s hard for me to be optimistic when I see, for example, the news about [the libel suit between] Fox News and Dominion. Those people knew they were lying. They didn’t believe that nonsense, but they still said it on the air. I don’t know what I find more depressing; that [lying] or the fact that people aren’t shocked to hear about it.”

The guitarist later recounted a visit he and Hubley made to the Lyndon Johnson Presidential Library in Austin, Texas, which made him think of “the idea of right and wrong.” Kaplan went on to note that “beyond the tremendous mistakes he made and the ugly political compromises he made, Johnson was trying to make the world better. I think Richard Nixon was trying, too. I’m afraid [former Fox News host] Tucker Carlson is not trying to make the world better.”

A few days later, at his Washington concert, Kaplan seemed to reflect further on that point when he stopped midway through one of his more playful songs, “Periodically Double or Triple,” which is about a cretin, and said, “In this day and age, when so many people will say stupid things that they don’t believe in just to get attention, we ask you not to lump us in with that because we’re singing these lyrics.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition