The craze for Spanish cuisine was unleashed by chef Ferran Adrià and his elBulli restaurant. In fact, August 10, 2003, should be etched in gold letters in the history books of Spanish gastronomy as the date when a certain New York Times journalist, Arthur Lubow, penned A Laboratory of Taste and credited Adriá with turning Spain into the new France. It was the springboard for what was to come: elBulli was named best restaurant in the world five times, El Celler de Can Roca twice, and Dabiz Muñoz has reigned as the best chef in the world for two consecutive years. TV reality shows have also contributed to the celebrity status enjoyed by chefs, more and more restaurants are opening and new cooking trends are emerging. And, of course, publishers have leaped on board.

Design and aesthetics

The publishing house, Phaidon, has long been recognized for its art and photography books. In 2007, they decided to bring that know-how to cuisine. Back then, there was no YouTube or social networks on which to upload videos, recalls Pedro Martín-Caro, Phaidon’s director in Spain. “They were selling cheap recipe books with food on the cover,” he explains.

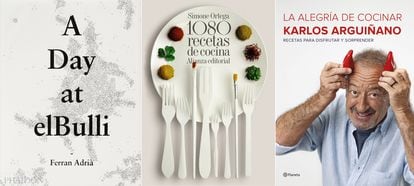

Phaidon decided to focus on the aesthetics, resurrecting a successful book from the 1950s in Italy called The Silver Spoon. “It’s a staple of Italian cooking, which has sold millions of copies in all the languages we’ve edited it in,” he says, adding that it put Phaidon on the gastro map. They then decided to replicate this model in other countries. “You take a country, such as Mexico, Turkey or Peru, and think of the dishes that people eat at home,” he says. Meanwhile, in Spain, they bought the English-language rights to Ferran Adrià’s A Day at elBulli in 2010. And two years later, How elBulli Works. Which, in turn, launched a series of chef’s books.

The chef as god

A recipe book is like a letter of introduction for many chefs. “It’s a communication tool,” says Javi Antoja, director of Montagud, a Barcelona publishing house founded in 1906. “Print is the traditional social network. It is the one that is most valid. We tell stories about the history of gastronomy that end up being a reference tool.”

He cites the 2002 book Bras, by French chef Michel Bras, as an example, which he says “is still relevant 20 years later.” The same goes for Sous-Vide Cuisine, by Joan Roca and Salvador Brugues, published in 2003 and now in its seventh edition in several languages, or Broths, a reference work by Valencian chef Ricard Camarena, published in 2015. “It is important that a book does not have an expiry date,” says Antoja. “When we see that an author has potential, we propose a project.”

“Our illustrated books are beastly, they take tons of paper,” adds Antoja. “But I’m very geeky and if I see that the project has soul, the economic aspect doesn’t bother me because it ends up being profitable. The most important thing is that it is unique, and that we invest in photography, illustration, printing and time.” Montagud does not skimp on resources. In the pipeline is a work on El Celler de Can Roca, another on Paco Roncero, Ramón Freixa and on the phenomenon of one of the temples of Catalan cuisine, Granja Elena. But the jewel in Montagud’s crown is The Practical Dessert Formula, a pocket book written in 1933 by Ramón Vilardell and José Jornet, in its 65th edition with more than 66,000 copies sold.

The chef’s book is inspiring: the author explains their creative process and shares the formula for preparing some of their dishes, which according to Martín-Caro, are nevertheless hard to replicate. He cites as an example the book Noma: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine. Noma, the restaurant, was chosen five times by Restaurant magazine as the best eatery in the world, although it will close its doors to become a food laboratory in Copenhagen at the end of 2024, as announced by its chef, Rene Redzepi. “Noma lives within a radius of 50 kilometers. It thrives on what’s around it, so it’s very difficult to replicate its recipes anywhere else in the world,” says Martín-Caro. Chef’s books are, at the end of the day, reference books, to be used in much the same way as an architect might buy a book by Le Corbusier and then build social housing.

Two phenomena: Karlos Arguiñano and Simone Ortega

In the 1990s, Karlos Arguiñano made a splash on TV. His popular program, A Menu for Every Day, soon produced a book. The Asturian publisher and writer Álvaro Díaz-Huici, head of Trea publishing, says: “When I was starting out in the book business, Arguiñano was very fashionable and the publication of his first book was put out to tender. I bid alongside another publishing house and we were on the verge of getting it, but we came second. I have sometimes asked myself: what would have happened if we had got that first book?” Because if there is one thing that is clear to this editor, it is that the Basque chef is “the smartest of all chefs, perhaps because he is the most normal, and has the least pretensions.” He connects with people, with readers. Planeta knows this and has developed a love affair with this chef from Zarauz in Gipuzkoa, with an annual recipe book published every year since 2010. “Every year he sells 100,000 copies, and he may have sold more than a million books,” says David Figueras, editor of Planeta Gastro. “People can’t get enough of him.”

Another phenomenon is Simone Ortega’s 1972 1080 Recipes, a classic among Spanish recipe books, which has survived passing fads and served as an apprenticeship to more than five million people, including renowned chefs, according to Alianza publishers. Ferran Adrià says that without Ortega, the current boom in Spanish cuisine would not have existed. After the author’s death, his daughter, Inés Ortega, took charge of revising the recipes and making them lighter.

Uneducated gourmets

According to Díaz-Huici, the key to Arguiñano and Ortega’s success lies in respecting cooking as a craft and technique. “It is not art,” he says. “It seems excessive the way some chefs have contaminated day-to-day cooking. It is not an elite cuisine.” Díaz-Huici avoids being sucked into the trends of the famous chef cookbook. “It doesn’t add anything,” he says. Instead, he focuses on the dissemination of gastronomic history and culture, and states that “there are many uneducated gourmets, mere glossators, tasters of dishes, swept along by a current that shifts a lot of money, but which is not invested in gastronomic knowledge.” The Trea collection includes titles such as Eating in Spain and From Subsistence Cooking to Cutting Edge Cuisine. “We publish historical recipe books, which are a reflection of an era,” he says. “You discover that industrial cuisine is not something that has just been invented, that the Italian cook of the Renaissance, Bartolomeo Scappi, in the service of several popes in the Vatican, was serving food for 400 people.”

The business boom

Publishers, like record label managers signing singers with potential hits, have smelled profit. “I’ve been a publisher at Planeta for 22 years and the biggest changes have been happening since 2015,” says Figueras. It was then that the publishing group created their gastro line. A year later, they printed their first gastronomic title, Bake it Simple, a volume of easy pastries with Oriol Balaguer. The publishing house now has a backlist of 120 titles and they launch an average of 15 new titles on cuisine a year. “We produce a book of a certain quality for a high price,” says Figueras. “We’ve also detected a demand for text.” Leaving aside Arguiñano, among the most popular are Mother Chef, a recipe book featuring 80 dishes by Joan Roca and his mother, Montserrat Fontané, which has sold 25,000 copies; also, the recipe books by Xabier Gutiérrez, who, until last year, was head of innovation at the Arzak restaurant; Vegetables Without Limits by José Andrés; and Papilas and Molecules: The Aromatic Science of Food and Wine, by François Chartier.

Although the market seems to have slowed down in 2022, it is still booming, according to Figueras. The publishers have drawn up their schedules until 2024. Cookbooks are not easy to put together. Competition is increasing, so “it is necessary to include an element of surprise.” They also need the complicity of chefs whose schedules are increasingly complicated. Most of the renowned chefs tend to have consulting and business engagements outside the restaurant. “They are like rock stars and that helps sell books,” adds Cristina Paricio, editorial director and co-founder of Cinco Tintas, a publishing house that included cuisine in 2015, with a cocktail manual, now in its seventh edition and with more than 15,000 volumes sold. To date, Cinco Tintas has 50 gastro titles on the shelves of bookstores. Paricio believes that the boom in cooking content is due to the “saturation of cooking topics on social networks, which has turned people onto the print experience.”

Producing a book can take one year, or five. It depends on many factors. As soon as demand is perceived, as in the case of a book on Mexican cuisine by chef Paco Méndez from Come restaurant in Barcelona, the machinery is set in motion: editors, photographers, designers, illustrators and cooks who know how to communicate. “It can go smoothly, but if it runs into problems, it can take up to five years,” says Figueras. “We work on at least 25 titles at a time.” Figueras knows what he is talking about: since 2019, Planeta Gastro has been working on a volume on seaweed with the Galician firm Porto Muiños. The dream is that one day it will actually adorn the shelf of a bookstore.

Instagram gastro

“The jaw is our best tool to grasp philosophical knowledge,” said Salvador Dalí in the cookbook Dalí. Les Dîners de Gala, first published in 1973, in which he shares the culinary secrets of the chefs of several Michelin-starred Parisian restaurants, such as Lasserre, La Tour d’Argent, Maxim’s and Le Train Bleu. It is more than a cookbook, it is a work of art, in which the influential artist, who wanted to be a chef, conceives of food as a sensory spectacle. Following trends is important, says Paricio, who has observed that books on vegetarian or vegan themes have run out of steam. “We’ve noticed a slight decline,” she says. “On the other hand, what is doing well is Asian cuisine, especially Korean.” The editor points to another trend. Just as chefs and restaurants have their own book, influencers with thousands of followers on Instagram are also looking to get their story in print.

This is the case of influencers Cristina Ferrer and Verónica Sánchez, who met on Instagram and have now published Cuisine for the Tribe. “Each publishing house has to find its identity, find its niche,” says Paricio. “Competition is good, but you have to distinguish yourself.” Paricio insists on the importance of the reader connecting with the book’s narrator. She points to the case of Robert Ruiz, author of Fermentar, which details the techniques of an ancient art: “It is a success because he is a great disseminator. We also know that if Dabiz Muñoz publishes a book, it will sell out. Not because he is famous, but because he generates content.”

The bookseller also seeks to have gems to set them apart from the rest as is the case of Sara Cucala, the entrepreneur who, together with two partners, opened A Punto in 2008, in the midst of the economic crisis. The bookstore specializes in cuisine, but also boasts an events space and cooking school, taking inspiration from a similar initiative in Notting Hill, London. “We were either visionary or crazy, but we are still here, looking for attractive and different projects.” Projects like the book by Bolivian chef Marco Antonio Quelca Huayta, The Clandestine Taste of the Concept Until it Becomes Reality. “We are the only ones who sell it,” she says. They know that collectors are on the prowl and that there’s a market for works such as this and Yoshihiro Narisawa’s Satoyama Cuisine, published by Taschen. Even if it’s being sold for €1,250. “It’s a jewel,” says Cucala.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition